Origins of the Style

Near the end of the 12th century, the Ōshu Fujiwara clan established a powerful 100-year dynasty in Hiraizumi, in what was then known as the country of Mutsu.

It is believed that Hidehira-nuri originated during this prosperous time, when the 3rd Fujiwara leader, Fujiwara no Hidehira, invited craftsmen from the capitol to create vessels using the abundant lacquer and gold produced in Iwate.

Characteristics of the Style

Hidehira-nuri typically includes a thick, durable base coating, with designs based off surviving “Old” Hidehira bowls. Typical elements include “yusoku” patterns, a combination of diamonds and strips of gold-leaf laid over cloud shapes that is emblematic of old Japanese nobility, and votive designs such as flowers that symbolize good fortune, speaking to wishes for good harvests and prosperous families. Drawn freely and repeating across the piece, the designs are not particularly complex, but have a simple elegance.

Hidehira bowls would typically come in a set of three; small, medium, and large. The shape of the bowls is rather wide with a gentle curve, and the bases tall and slightly flared.

The bowls were originally created as tableware for guests of the home during ceremonial occasions, such as weddings. The variation in patterns that was used from household to household is another interesting hallmark of the style.

In the Hiraizumi area, these pieces are affectionately known as simply “Hidehira bowls,” and some longstanding local families have passed their house’s down for generations.

Among the oldest such bowls are several dozen that still survive from the 16th century, the Azuchi-Momoyama period.

The History of Hidehira-Nuri

Hidehira-nuri emerged as a style in the late Heian period, at the end of the 12th century. Fujiwara no Hidehira, the 3rd leader of the Ōshu Fujiwara clan and lord of a prosperous, peaceful Hiraizumi, enticed skilled craftsmen from the capital of Kyoto to create lacquerware for him using Iwate’s abundant supply of lacquer and gold.

The mastery of these artisans is on full display in Chūson-ji Temple’s Konjikidō, or Golden Hall, part of the World Heritage Registry. The interior is richly decorated with gold leaf, gold and silver dust lacquer painting, and mother-of-pearl.

We also have seen evidence of lacquerware production in supplies found at Kyara no Gosho and Yanagi no Gosho, such as brushes, paint scrapers, and straining paper. In all, it’s evident that skilled lacquer artists regularly plied their trade in the Heian-era Hiraizumi.

Surviving “Old” Hidehira Bowls, as they are known in the area, have mostly been passed down by farming families in the region around Hiraizumi.

The oldest surviving pieces date from the Azuchi-Momoyama period in the 16th century, with other examples slightly younger, from the Edo period.

During the Meiji and Taisho years, the region’s lacquerware industry continued to expand, and to meet demand, workshops pivoted to plainer-decorated bowls and tableware, which were circulated under the name of “Masuzawa Lacquerware.” With the decline in production of more elaborate Hidehira-nuri pieces, the techniques to make it were also gradually lost.

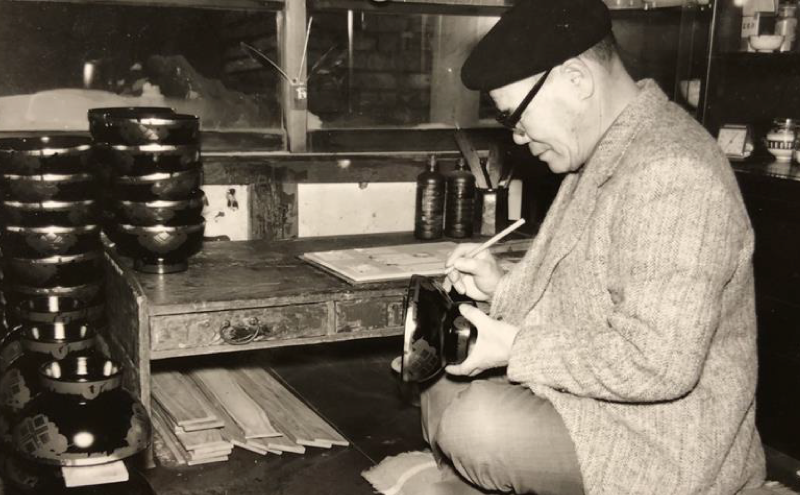

Then, in 1945, the second generation owner of Ochiya, Makoto Sasaki, began studying Hidehira bowls and their gold-leaf applique, and used them to recreate the historical techniques and revive the tradition of Hidehira-nuri bowls. His work was exhibited at the Nihonbashi Takashimaya department store in Tokyo, where it was very well received.

At the exhibition, Muneyoshi Yanagi, an activist and folk art proponent, was very impressed with the pieces, and traveled with a group of researchers to visit the Masuzawa area in Koromogawa village, where they were made.

His visit brought the simple, yet elegant Hidehira-nuri lacquerware to the attention of the public, and pieces were spotlighted in many publications, and exhibited at the Japanese Folk Art Museum.

After that, the production of Hidehira-nuri pieces returned alongside the ongoing Masuzawa lacquerware.

Creating Hidehira-nuri Lacquerware